Blog

Thermal energy demand intensity—or TEDI—is the new kid on the block for evaluating building performance and has worked its way into several major building codes in North America.

In this blog post, we’re exploring the definition of TEDI, its application in building energy codes, and key considerations when using it to inform building design.

TEDI refers to the total amount of thermal energy a building requires for space heating, expressed on a per-unit-area basis (typically in kBtu/ft2/yr or kWh/m2/yr). It reflects the amount of energy output from all heating systems in the building that are used to maintain comfortable indoor temperatures.

The primary factors that affect TEDI are building design and massing, envelope assembly performance (including thermal bridging effects), ventilation, energy recovery, internal loads, and local climate. It should be noted that cooling demand can also be used to define an alternate TEDI metric to evaluate space cooling performance of the building.

The lower the TEDI, the less energy is needed to heat the building—signaling better performance. By focusing on TEDI, design teams can look to optimize passive solutions such as envelope performance, mitigating thermal bridging, improving air tightness, and optimizing ventilation systems.

TEDI has recently become an important metric in building energy codes due to its focus on improving the thermal performance of buildings. Local building energy codes around the world are beginning to require project teams to meet specific TEDI thresholds for new construction or major renovations.

In these codes, TEDI is often integrated as a part of a whole-building energy performance approach in combination with other metrics such as energy use intensity (EUI) and carbon emission reduction (greenhouse gas intensity, GHGI). By incorporating TEDI, building codes aim to ensure that buildings are designed to use as little energy as possible for heating purposes, contributing to broader goals of energy conservation and climate change mitigation.

Some notable examples of building codes that incorporate TEDI include:

When implementing TEDI as a metric within building energy codes, there are several critical factors that need to be considered to ensure it serves as an effective tool for improving energy performance.

All of the factors below affect how TEDI thresholds are developed and determined by municipalities, government organizations, and other authorities having jurisdiction. Specific and detailed energy modeling guidelines that are tailored to modeling for TEDI threshold compliance are critical to ensure consistent results across all energy modeling, allowing for a fair comparison between building performance and design.

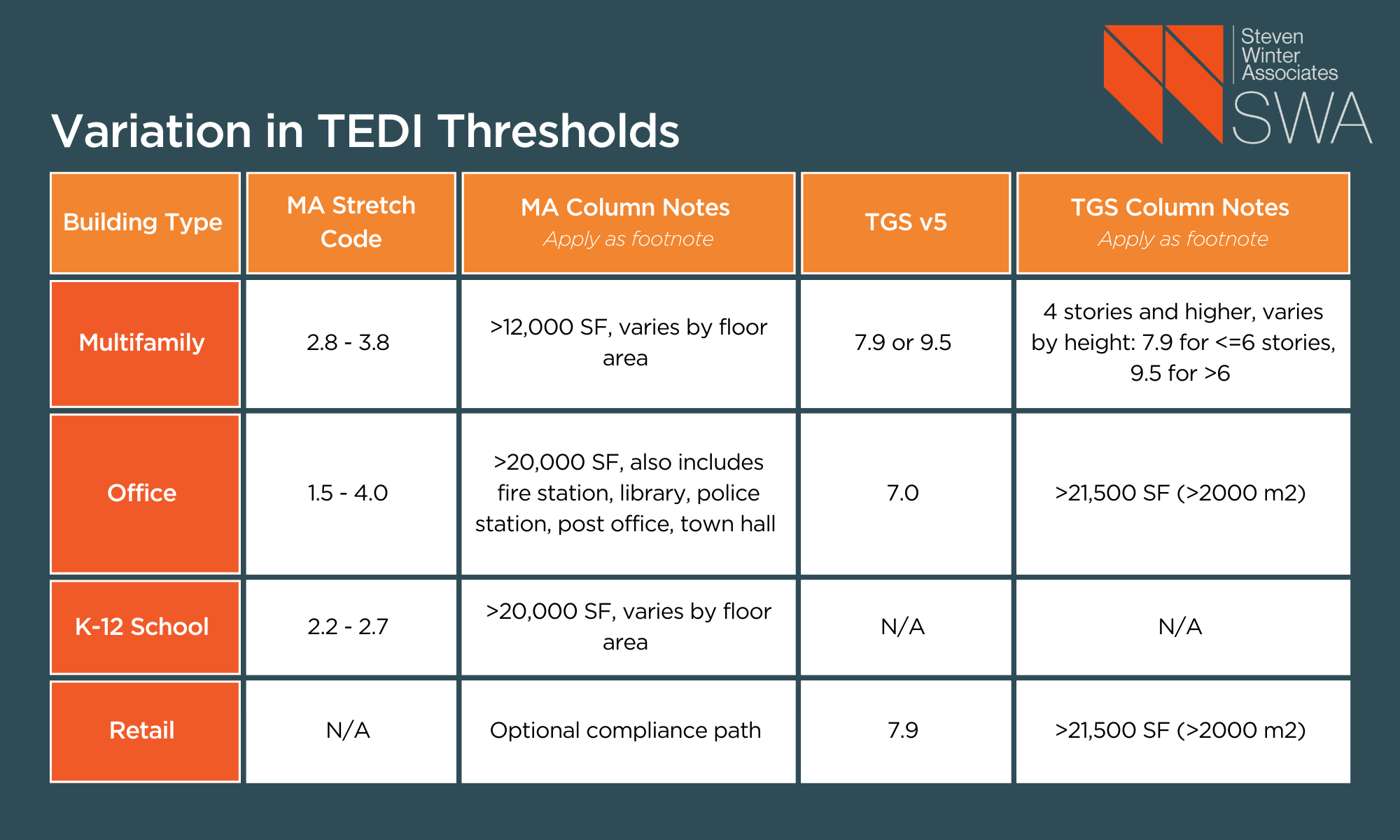

For example, the development of the TEDI thresholds for the Toronto Green Standard and Massachusetts Stretch Code was undoubtably different and therefore, resulted in different energy modeling guidance for each code. Knowing this, and the variation in climate between Toronto and Massachusetts, we see the following variation in TEDI thresholds for each energy code:

The thermal energy demand of a building is highly dependent on the climate in which it is located. Buildings in colder climates will naturally have higher thermal energy demands than those in warmer regions. Therefore, TEDI thresholds may vary depending on location, with energy codes often adjusting the target values based on local climate conditions.

To provide consistency when evaluating TEDI, energy modeling guidelines typically provide weather files to use in energy modeling based on the location of the project.

The building’s envelope—the walls, roof, floors, windows, and doors—plays a significant role in determining its thermal demand. A well-insulated building with thermal bridge mitigation, high-performance windows, and airtight construction will generally have a lower TEDI compared to a building with a poor-performing envelope.

As such, TEDI-based energy codes can drive the adoption of advanced insulation materials, better window technology, thermal bridging mitigation products and solutions, and more airtight construction practices.

The amount of outdoor air delivered to a building and the manner in which it is delivered has a significant impact on TEDI. The presence and effectiveness of heat recovery ventilation (HRV) or energy recovery ventilation (ERV) will affect how hard the rest of the building’s heating systems have to work in order to maintain comfortable indoor conditions.

Optimized control of ventilation systems, including delivery based on demand or occupancy (demand-controlled ventilation, DVC) and supply air temperature setpoint control, will also impact TEDI.

Thermal energy demand is also influenced by internal heat gains and their operating schedules, such as those from appliances, lighting, and occupants. Buildings that contain a large amount of equipment, are heavily used, or have a high density of people will have lower space heating needs than buildings that are sparsely occupied and have low internal heat gains.

Properly accounting for internal gains in the TEDI calculation is essential for achieving accurate assessments of a building’s energy demand. To provide consistency and avoid project teams utilizing high internal gains to drive TEDI down, energy modeling guidelines typically prescribe values to use for internal gains as well as operating schedules to use in energy models.

Larger buildings or those with complex designs may present challenges when optimizing TEDI. However, advancements in building modeling and simulation tools allow architects and engineers to design for low TEDI even in larger or more intricate buildings.

The layout, geometry, and orientation of a building, as well as how it is divided into spaces (e.g., open plan vs. compartmentalized), will all influence its thermal demand. In general, as exterior envelope area (normalized by floor area; this is called the “form factor”) increases, so does TEDI.

Thermal energy demand intensity (TEDI) is an essential metric for understanding and improving the overall performance of our built environment. By incorporating TEDI into building energy codes, governments and regulators are able to encourage the construction of buildings that consume less energy for heating (a driver of performance in cold climates), are more comfortable for occupants, and reduce operating costs for owners.

However, to effectively apply TEDI in building design, it is crucial to consider a range of factors, including climate, building envelope, heating system efficiency, and occupancy patterns. By understanding TEDI’s role and considering these key factors, architects, engineers, and policymakers can create buildings that are not only energy-efficient but also resilient to the challenges of a changing climate.

Our sustainability consultants in Massachusetts and Toronto will work with you to achieve compliance with local building energy codes in the most efficient and cost-effective way possible. Fill out our contact form to get started today.

Contributor: Matthew Hudson, Senior Energy Engineer

Steven Winter Associates